Hasekura Tsunenaga

Dipinto presso il palazzo Borghese a Roma raffigurante il Samurai Hasekura Tsunenaga

primo ambasciatore ufficiale giapponese alle Americhe e Europa nel 1615.

Lo scultore Nobuyuki Okumura e l'Ing. Novello Cavazza

discendente di Papa Paolo V, nato Camillo Borghese,

che ricevette la prima ambasciata giapponese nel 1615.

|

Papa Paolo V nato Camillo Borghese

|

Tratto da Wikipedia

L'ambasciata giapponese arrivò in Italia, dove riuscirono ad ottenere udienza da Papa Paolo V a Roma, nel novembre 1615. Hasekura consegnò al Papa una preziosa lettera decorata d'oro, contenente una formale richiesta di un trattato commerciale tra Giappone e Messico, oltre che l'invio di missionari cristiani in Giappone.

Il Papa accettò senza indugio di disporre l'invio di missionari, ma lasciò la decisione di un trattato commerciale al Re di Spagna. Il Papa scrisse poi una lettera per Date Masamune, della quale una copia è a tutt'oggi conservata in Vaticano.

Il Senato di Roma conferì a Hasekura il titolo onorifico di Cittadino Romano, in un documento ch'egli successivamente portò in Giappone e che oggi è ancora visibile e conservato a Sendai.

Lo scrittore italiano Scipione Amati, che accompagnò l'ambasceria nel 1615 e nel 1616, pubblicò a Roma un libro intitolato "Storia del regno di Voxu".

Nel 1616, l'editore francese Abraham Savgrain pubblicò un resoconto della visita di Hasekura a Roma: "Récit de l'entrée solemnelle et remarquable faite á Rome, par Dom Philippe Francois Faxicura" ("Racconto della solenne e notevole entrata fatta a Roma da Don Filippo Francesco Faxicura").

dettaglio del dipinto presso Palazzo Borghese

Hasekura Tsunenaga,

first official Japanese mission to Europe

On my way back to Rome's Fiumicino Airport Civitavecchia, I detected from the car window a statue of a Japanese samurai

standing by the road in a small village we were passing through. I asked the

driver to stop, and discovered what was unmistakably a statue of samurai

Hasekura Tsunenaga, who was sent to Europe as the Head of the Japanese mission,

some 400 years ago. I knew that Hasekura Tsunenaga had visited Rome but I was

not aware exactly where he had arrived in Italy. I need to investigate further

but my sense of judgement at the time of writing this blog (during my return

flight to London) is that he might have landed at the exact place where his

statue is raised.

Readers of my blog will know that I am very interested in maritime heritage and maritime history - I blogged about

the story of John Manjiro on 29 January this year - and I am encouraging

my colleagues to bring good maritime histories to the attention of people and

the general public, in order to attract their attention to our wonderful

maritime history and maritime heritage. I believe that this is a good and

effective way to highlight the importance of shipping and international trade

in our life today, and that public awareness of IMO's activities can also be

enhanced by understanding this historical context. I am personally very

interested in this way of seeking and promoting our outreach activities.

In 1600, the Englishman William Adams landed on

the western island of Japan because his ship, the Dutch vessel De Liefde, had

run aground and been wrecked. He survived, and passed on his knowledge of

western shipbuilding technology to Japan. He served Shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu and

himself became a samurai, Miura Anjin - the first and last Englishman to

be a samurai. He built two western-style sailing ships with Japanese

shipbuilders. One of them, the San Buena Ventura, was given to the then Spanish

General Governor of the Philippines, Rodrigo de Vivero, to enable him and his own

ships' crew - who had also been shipwrecked on the coast of Japan -

to return to the Spanish territory in America which is now known as Mexico.

Tokugawa Ieyasu was interested to promote trade

with Spain and attempted to contract a treaty, but it never came to fruition.

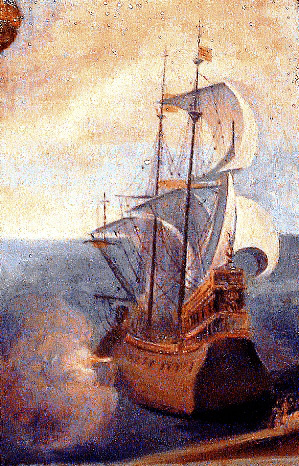

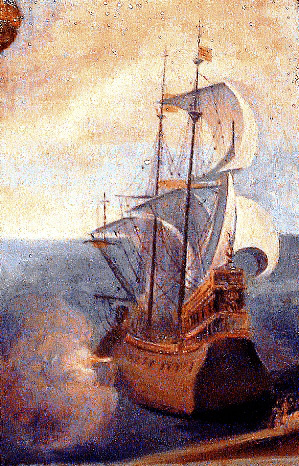

Another warrior chief, daimyo Date Masamune, shared the ambition of Ieyasu and

also built a galleon-style ship, the San Juan Bautista, using the technology

passed to the Japanese by William Adams. He sent this ship on a formal mission

to Spain, in 1614 - 400 years ago. There is a replica of this ship in

Ishinomaki, in the northern part of Japan. The replica was caught up in the

tsunami of 2011 but survived and is now on display to the general public in a

maritime museum in Ishinomaki.

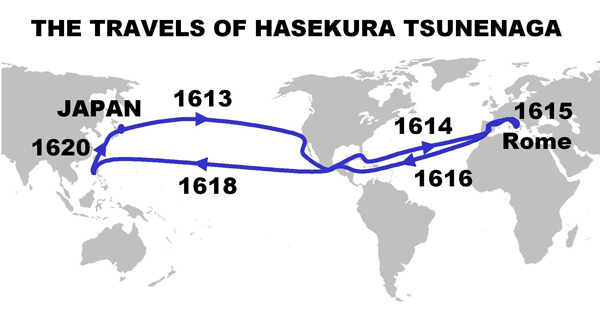

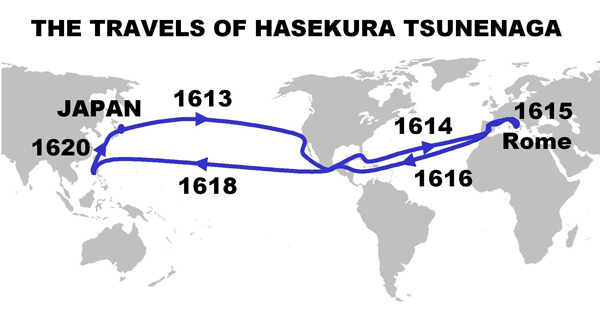

The head of that mission was Hasekura Tsunenaga

and, as his mission navigated eastbound through the Pacific Ocean from Japan,

he called at Acapulco in Mexico. The mission then travelled further eastwards

and, on arrival in Spain, he met King Filipe III. The mission continued

eastbound and eventually arrived at Rome where Hasekura Tsunenaga met the Pope,

Paulus V, and received the honorary title of Roman Citizen.

Eventually he turned back to Japan via the

present-day Mexico and through the Pacific Ocean; but when he arrived home,

Christianity had been already prohibited in Japan and the country was

eventually closed against foreign countries, except for a window in Nagasaki

for the Dutch people. Thus the objective of Hasekura Tsunenaga's mission, to

open trade with Spain, was not realised.

Today, in 2014, I saw, by chance, the statue of

Hasekura Tsunenaga near Civitavecchia. Standing in front of the statue, I

really felt the power of our remarkable maritime history; and it helped me to

see the crucial work carried out by IMO for the maritime community in the 21st

century in its true historical perspective.

Koji

Mr. Koji Sekimizu

Secretary-General

IMO International Maritime Organization

www.imo.org